In the intricate web of global value chains, forced labor emerges as a stark embodiment of modern slavery, entrapping millions in invisible chains of exploitation. The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines forced labor as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.” This definition, while straightforward, encompasses a complex reality where coercion, deception, and abuse of power anchor individuals in oppressive work environments. The eradication of forced labor is not only a moral imperative but a critical step towards sustainable and ethical business practices. Yet, auditing for forced labor within ESG frameworks reveals a labyrinth of challenges, demanding auditors to refine their approach, especially in the nuanced art of interviewing.

The Significance of Eradicating Forced Labor

Forced labor is a blight on human dignity and rights, posing significant ethical, legal, and reputational risks to businesses. In today’s conscientious market, the presence of forced labor within value chains can lead to severe consequences, including legal sanctions, boycotts, and loss of consumer trust. Beyond compliance and reputation, addressing forced labor is about upholding the fundamental rights of individuals and fostering a fair, equitable working environment. It’s about businesses taking a stand against exploitation, contributing to a more just and humane world.

The Complexity of Auditing Forced Labor

Auditing for forced labor is akin to navigating a complex maze with hidden traps. Forced labor often operates under layers of subtlety and deceit, with coercion and fear silencing victims. Traditional audit methods, reliant on document reviews and facility walkthroughs, may only scratch the surface, missing the covert indicators of exploitation. The complexity is compounded by global supply chains’ intricate and transnational nature, making visibility and accountability challenging to maintain.

Leveraging Interviewing Skills and ILO’s 11 Indicators

Auditors, equipped with acute interviewing skills, can penetrate these layers, unearthing the hidden realities of forced labor. The PEACE model, with its emphasis on preparation, engagement, and account, provides a structured approach to interviews, encouraging openness and trust. Through empathetic and culturally sensitive interviewing, auditors can create an environment where workers feel safe to share their experiences.

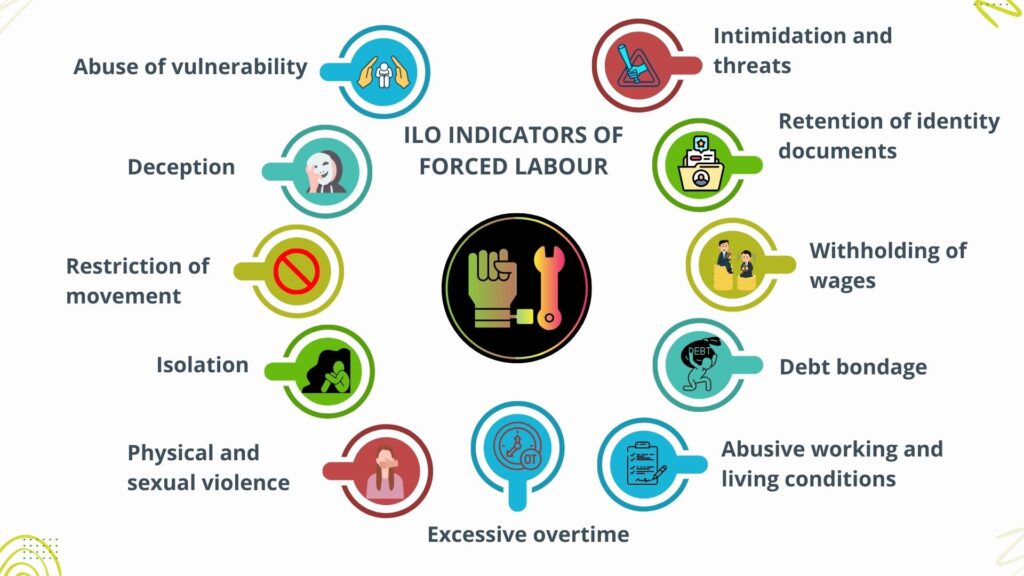

The ILO’s 11 indicators of forced labor are instrumental in guiding these conversations. These indicators include abuse of vulnerability, deception, restriction of movement, isolation, physical and sexual violence, intimidation and threats, retention of identity documents, withholding of wages, debt bondage, abusive working and living conditions, and excessive overtime. Each indicator offers a lens through which auditors can explore potential abuses, framing questions that probe into workers’ conditions and experiences without direct accusation or confrontation. For instance, auditors might inquire about workers’ freedom to leave their job or the conditions under which their identity documents are held. Such questions, posed with tact and sensitivity, can reveal the nuanced practices of coercion and control characteristic of forced labor.

The Value Added by Auditors

Discovering forced labor issues through audits transcends the mere identification of non-compliance; it’s a critical step towards remediation and prevention. Auditors, by uncovering these issues, catalyze change, prompting organizations to address the root causes of forced labor, implement corrective actions, and foster more transparent, ethical operations. This not only mitigates legal and reputational risks but also contributes to the global fight against modern slavery. Furthermore, by bringing these issues to light, auditors empower victims, initiating processes that can restore their rights and dignity.

The auditor’s role in identifying forced labor is a testament to the profound impact of diligent, informed, and empathetic audit practices. It underscores the auditor’s contribution to a larger ethical mandate, advocating for human rights and dignity within the sphere of global commerce. Through their meticulous work, auditors are not just enforcing compliance; they are champions of change, driving the industry towards greater transparency, accountability, and respect for human rights.

Conclusion

The challenge of auditing forced labor within ESG frameworks is daunting, yet undeniably crucial. It requires auditors to navigate complex realities, leveraging their interviewing skills and a deep understanding of forced labor’s indicators to uncover hidden abuses. The significance of this work cannot be overstated. By identifying forced labor, auditors not only facilitate compliance and protect businesses from reputational harm but also contribute to the global endeavor to eradicate modern slavery. Their work shines a light on the shadows of exploitation, guiding businesses towards ethical practices that respect and uphold human dignity. In the realm of social compliance auditing, the fight against forced labor is a pivotal battleground, one where auditors play a leading role in shaping a more ethical, equitable, and humane global economy.